The roar of the bomber jets overhead woke me up early this morning. The supersonic rumble broke the dawn and everything seemed to begin. “They are on their way to Homs”, I’m told. Being this far out in the valleys and farms I had imagined the sound of roosters or lambs might be my reveille but this is Syria in 2017.

They didn’t seem to take a break today from the bombing but planes passed over barely noticed by villagers. Like living next to a railway, the din becomes eerily customary. What will never go unnoticed are the signs of war; posters for the sons, brothers, fathers and men of the village who have given up their lives. Memories of these brave men will not be soon forgotten.

We had power for an hour last evening and mobile phones, laptops, flashlights and all things with a battery were quickly connected and charging. On full charge until morning when there will be another quick shot of power if there are no surprises. The word surprise for a child back home brings anticipation, excitement, maybe even wonder. The word doesn’t necessarily elicit the same feelings here.

It was a special day in Baytanna and I didn’t want to oversleep. Meaning “home to the gods,” Baytanna is a few hundred kilometres from the conflict and about forty from the nearest large city, Latakia. The day began with some hunting, a roadside breakfast, tea made with herbs and mountain spring water, followed by Yerba Mate and shisha (or Arguila as it is called here) at a mountain top park. It’s late winter and the pruning is done. The terraced ground has been turned over in neat rows and the first signs of spring are pushing out. Thousands of years farming this land have turned every impossible slope of the valley into topographical terraces held by solid stone walls cut from the quarries dotting the valley floor. The pace is neither fast nor slow here. The pace just is.

This area is a gardener’s dream with a temperate South Mediterranean climate hosting four distinct seasons. Cool winters bring only a rare bit of snow. Glorious spring weather is followed by warm summers and a moderate fall. It seems as though everything grows here. All types of citrus — even pomelo — tender fruits, figs, nuts, grapes and berries. For anyone still on a hundred mile kick, bananas from the coast are a unique menu addition.

Stunning olives, mostly green, but all flavour. Olive oil is a way of life here for salads, sauces, skin care and soaps. “That’s why people are so young and beautiful in Baytanna,” I’m told. Pork is taboo but available. Lamb, chicken and beef are the meats of choice as are seasonal game birds, although meat in general is used sparsely. Quite common is bulgur. Don’t make the mistake of calling it couscous or you might hear a guarded snicker. “Cous” is slang for a female body part. Bulgur, wheat, corn, lentils, nuts, chickpeas and fava beans are much more popular than meat. Cucumber, tomato, romaine, onions, garlic, parsley and fresh herbs are staples used abundantly. Everything else is seasonal. Pickles are still made in most homes and the brightly pink coloured turnip pickles are enjoyed at almost every meal.

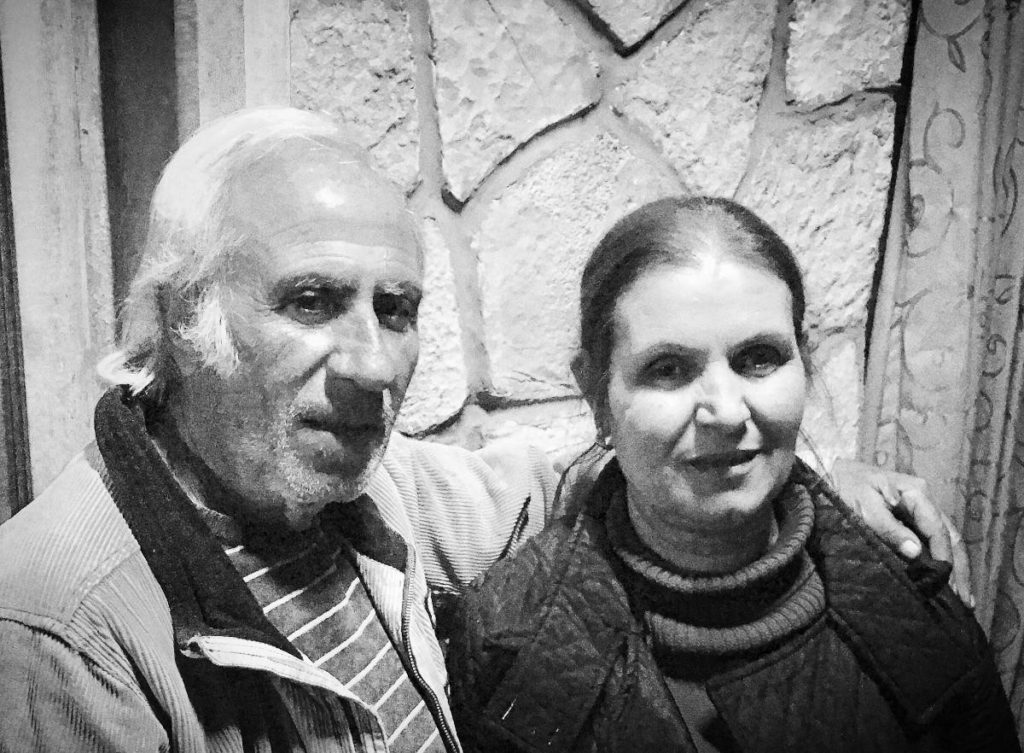

With an abundance of local food options, restauranteurs Abu Ayham and Hanan started their newest venture, Jofeen Cedar, in 2006 before the troubles began. They didn’t enter the business as rookies. Previously they operated a much more modest venue in the bottom of the valley before establishing their mountain top destination, designed as a huge hall and restaurant. Here they host massive weddings and parties and even served President Assad who came for a simple meal of lentils and vegetables. He still praises the couple.

Everything comes from the valley. With road blocks and gas scarce and expensive, it doesn’t make sense to truck in anything. Operating with electrical power for 1-2 hours per day means you have to conserve energy and run creatively. But with ingredients like olives, olive oil, nuts, spinach, greens, figs, apricots, apples, cheese, fresh butter, tomatoes, pomegranate, grapes, lamb, beef, fish and honey, the food options are plentiful.

The bread of choice here is called khubz… outside the Middle East, most would call it wholewheat pita. It’s standard across the Arab world. Like everything here it is made in house. Even the charcoal is made out back in a big smouldering pit of oak, earth and sand. “With only a bit gas and often no power, how to cook? Use charcoal. No charcoal…then you must make it,” says Abu Ayman, whose charcoal smoulders in a pit for 40 to 48 hours.

One of my favourite dishes from the Syrian kitchen is mutabel. Mutabel is a dip like hummus but combines roasted eggplant, yogurt, garlic, olive oil and salt. This dip will rival any other you have tasted. The recipe that follows is from local Chef Durid Dunia. He learned to cook from his mother who learned to cook from her mother and so on and on.

Syria is a beautiful country, spoiled by conflict. Regardless of the powers at odds the people want peace, which everyone hopes will soon come to restore the country.