Some books on non-European cuisines are best used as sources of recipes resembling cute, friendly Third World kids waiting to be scooped into adoptive Western parents’ arms: tabboulehs and pad Thais and raitas that fit in among mainstream classmates as if they’d always been there. The real mettle of other works lies in persuading the reader-cook to be the one who journeys — at least via cooking-spoon and saucepan — into another quadrant of the universe. Naomi Duguid’s book on the food of Burma, or Myanmar, belongs to this challenging company.

In a way the emphasis on directing North American users to a whole new frame of reference is even stronger than in the last few books by Duguid and her former husband, Jeffrey Alford – absorbing, adventurous photographic treks through great swaths of Asia by way of food. Burma: Rivers of Flavor is also absorbing, adventurous and photographically rich. But unlike its predecessors it is framed as a detailed, systematic introduction to one nation’s culinary heritage. To any question that cooks like me may have had about whether Burmese cuisine amounts to anything more than a patchwork of borrowings from India, China and a few Southeast Asian neighbours, it delivers a resounding yes.

Burmese cuisine has been well nigh impossible to explore over several decades of harsh political repression that more or less extinguished communication between Myanmar and the rest of the world regarding food or anything else. Among prior works published in this country only Mi Mi Khaing’s Cook and Entertain the Burmese Way and Copeland Marks and Aung Thein’s The Burmese Kitchen — both long out of print — offered much sustained insight and neither comes close to Duguid’s enlightening perspective.

The aforementioned patchwork question, and the way in which she answers it, are at the heart of the matter. Arguably any nation’s cuisine is a heterogeneous amalgam of elements lumped together inside borders drawn on a map. But some other kind of lightbulb gets turned on when you start understanding certain historic amalgams — French or Italian food, for instance — as national cuisines in their own right.

Duguid’s pathbreaking work places Burmese food in the company of the world’s most remarkable cuisines by pegging away at strategic underpinnings of flavour and technique more thoroughly than any prior English language treatment of the subject. True, it also offers a brief “Burmese Food in a Western Context” section where the casual-dipping school can find suggestions on the lines of “For Vegetarians,” “For Meat Lovers” or “Weeknight Supper Combos.” But you’ll be doing yourself a favour by ignoring this (at least for the moment) and getting systematically immersed in Duguid’s “rivers of flavour,” starting with the initial chapter on basic building blocks.

What you’ll find there are indispensable preparations that will crop up again and again in other dishes: peanuts roasted from scratch and coarsely chopped, nutty-flavoured toasted chickpea flour, dried shrimp ground to a powder, and more. You’ll later encounter these key players married with chopped fresh hot chiles, ginger, garlic, lemongrass and perhaps most important, lovely doses of minced or sliced shallots and freshly squeezed lime juice that are as indispensable to the general local flavour palette as onion-pepper-tomato sofritos would be in Spain.

A good next stopping place would be the chapter on condiments where I suggest exploring more complex Burmese flavour balances or juxtapositions through a dish titled “Raw and Cooked Vegetable Plate.” You assemble handfuls of parboiled or uncooked vegetables from Duguid’s suggested list, make a couple of the accompanying table sauces presented in the chapter, and set them out together. It’s a brilliant instant lesson in the tangos that fermented fish and shrimp pastes or tamarind pulp can dance with members of the chile-garlic-shallot lineup.

From there I suggest proceeding to the chapter called “Salads” — rough English shorthand for thoke, a quintessentially Burmese tribe of “hand-mixed dishes.” To taste how the layering of flavours and textures in these imaginative creations essentially depends on the earlier “basics” is to get still deeper clues to the structure of the cuisine. And before trying to wade into recipes based on fish/seafood, chicken, meat or vegetables, I’d next spend some time with the almost equally illuminating chapters on rice (the central pillar of the diet) and noodle dishes (everyone’s favouite street food).

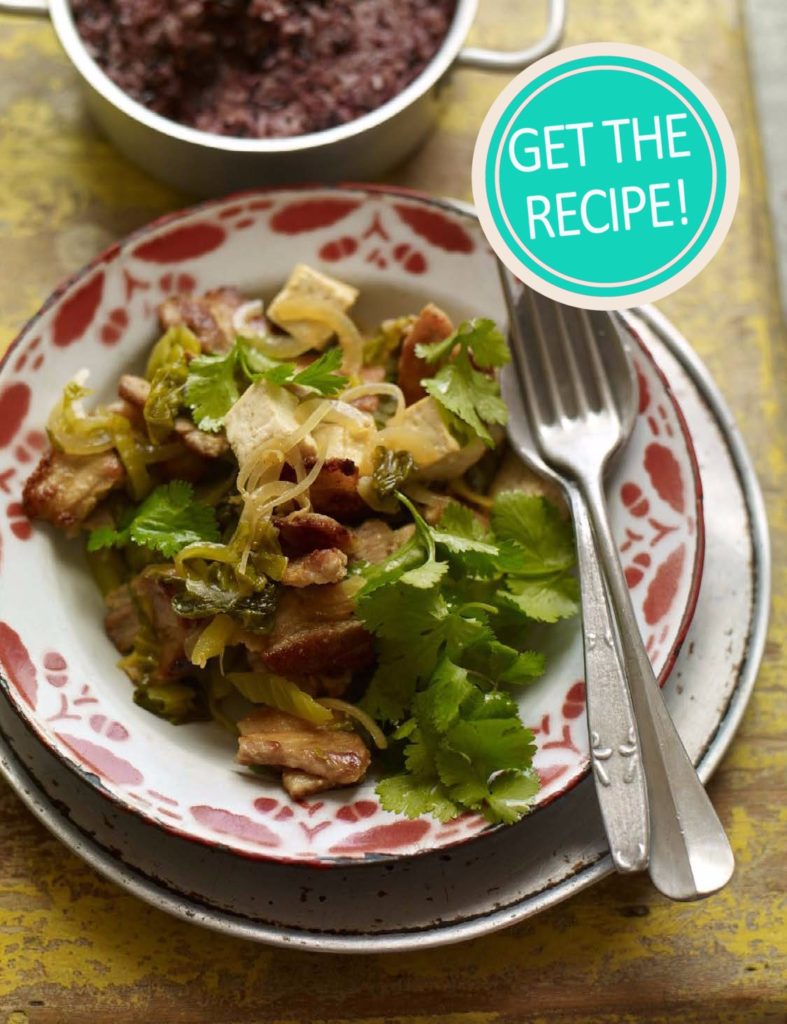

Once I’d begun preparing such basics as toasted rice powder or crisp-fried shallot shreds (with the flavourful oil they’re cooked in), I didn’t want to stop cooking from this book. Best of all were a condiment billed as “Pungent Essence of Burma” (funkily redolent of fish paste), an aptly titled “ambrosial chicken broth” (with briefly simmered shallots and an exhilarating dose of lime juice) and a silky, filling congee made from boiled peanuts and rice pureed together. (These last two providentially kept body and soul going in my house during the cold, dark aftermath of Hurricane Sandy.) I can also whole-heartedly recommend a “refresher” of slivered cabbage and shallots, punchy little “sliders” of minced pork, a brightly flavoured chicken salad, boiled eggs peeled and fried before being heated in a tomatoey curry sauce, stir-fried rice with crisp shallots, and a simple pureed bean-and-shallot soup perked up with leafy greens (I used watercress). Not a dud in the lot.

It’s only fair to mention that Burma: Rivers of Flavor has liabilities as well as strengths. From a reader’s viewpoint, the main problem is that what could have been tremendous amounts of valuable information on history, culture and politics seem to have been shrunk to mini-paragraphs and sentences and hastily stuffed into chinks throughout the book with or without strategic clues in the index. The glossary has been used as a bulging-at-the-seams storeroom for much of this material, especially on some of Burma’s many ethnic minorities. The bibliography is also called on for double duty but in that case the result is almost worth the price of admission in itself — I don’t know where you’d find a cookbook bibliography filled with as many kinds of thoughtful or even passionate historical and political perspective as Duguid supplies here.

From a cook’s viewpoint there could have been much more helpful guidance on finding and using crucial ingredients for users generally unfamiliar with southeast Asian cuisines. True, they can troll through the glossary for chunks of information, but presenting more “service” and shopping advice in one consecutive block would have been a real blessing.

None of these criticisms diminishes the book’s importance. It would have been a major contribution to the Asian cookbook literature in any event. But coming as it does at a moment promising more free communication between Myanmar and the outside world than has been possible since 1988 if not much earlier, it feels like an especially vivid part of a Burmese spring. Pack your bags — shopping bags, that is — and set out for extraordinary new rivers in the lively company of Naomi Duguid.

See all of our cookbook reviews on Pinterest!