Suriname. It’s a name that draws a blank from even the most well-travelled. Call it the former Dutch Guiana, and some can place it in the western hemisphere: a wedge penciled off the northern reaches of the Amazon rainforest; a mangrove-armoured coastline, barely accessible but for the rivers that pierce their way to the Atlantic. It’s a country in South America, but not of it – peopled originally by the Caribs and Arawaks, mostly bypassed by the Spanish, and thus sharing little, culturally, with the majority of the continent. Instead, the vagaries of history brought Dutch plantation owners and West African slaves to its shores; after abolition, workers from India, China, and Java. Centuries of mingling and mixing have created a true cultural pastiche — and a unique cuisine to match.

Nowhere is this fusion of ethnicities and flavours more apparent than in Suriname’s capital. A city of some 250,000 that sprawls across the Suriname River flats, Paramaribo boasts an 1842-inaugurated synagogue adjacent to its largest mosque, and a central core of Dutch-Creole wooden architecture that is a UNESCO World Heritage site. At its heart is Fort Zeelandia, Paramaribo’s oldest building (1640) and home to both the national museum (with a stellar collection of pre-Columbian and Amerindian artefacts) and the atmospheric Baka Foto (with its river terrace restaurant and courtyard brasserie). From here, the breezy waterkant, dotted with cafes, stretches through to the city’s Central Market.

There’s no better place to become grounded in the cuisine than in one of Paramaribo’s markets, where vendors offer all manner of fresh and saltwater fish, squashes, hot peppers and tropical fruit: think rambutan, tamarind, pomelo, and sterappel. Greens feature prominently in Surinamese cooking, including the colossal tajerblad (arrowleaf elephant ear) — boiled as a side-dish or chopped into soups — and the ubiquitous kouseband (or yard-long beans), which appear in everything from Indian-style masalas and Chinese stirfries to Javanese petjel and Dutch-inspired stews.

The Kwatta market provides our first insight into the dominant Javanese influence on local cuisine, as we queue up among the vendors of nasi (fried rice) and bami (fried noodles) for dawet, an iced beverage of lemongrass syrup and coconut milk, studded with tapioca pearls. Javanese cafes abound throughout the country, and sate and loempia (Javanese spring rolls) are sold as snacks everywhere.

Travellers to Suriname will find a phrasebook a useful accessory, as Dutch continues to be the official language and Sranan Tongo — a European- African creole — is common on the street. Speak English and you’re sure to raise heads; daily direct flights from Amsterdam mean that the tourist population is also primarily Dutch. English is a popular third language, however, and although the menu at Suriname’s home-grown roti restaurant chain, Grand Roopram, is Dutch-only, the English-speaking staff are happy to help you decipher it. Here the strictly-local crowd attests to the authenticity and quality of the chicken and vegetarian masalas, which are scooped from plate to mouth, sans cutlery, with soft folds of roti flatbread. Dishes of Indian origin in Suriname seem to find their primary expression in roti shops, but Martin’s House of Indian Food, just outside the city core, ramps up the variety with tasty biryanis, tandoori, and dals.

Moksi aleisi means “mixed rice” in Sranan Tongo, and this Surinamese menu staple — prepared with salt beef, dried shrimp, tomatoes, and a cook’s choice of local herbs and vegetables — has its origin in 17th– century slave culture. At Rode Ibis restaurant, the moksi aleisi arrives with a side of chicken, but on the riverfront deck of Cafe Broki, it finds an additional accompaniment by way of pom. Commonly served at Surinamese weddings and birthdays, pom is credited to early Portuguese-Jewish plantation owners, who replaced the traditional potato base of this citrus-juice-and-tomato-laced mash with the more readily available grated tajer root.

Suriname’s once-prolific plantations have declined since the end of the 19th century to little more than a handful of romantically derelict mills and warehouses. Notable exceptions include its sole remaining coffee producer, Plantage Katwijk (open for tours), and the extensively restored Plantage Fredericksdorp, which offers heritage accommodation and an excellent cafe amid its sprawling gardens. Fredericksdorp is accessible only by boat, but our Bentley Rondvaarten charter from Paramaribo provides an opportunity to see the pink-bellied Guiana dolphins that fish the estuary, while attentive owner William Ritfeld serves up commentary on the riverbank sights — as well as slices of bojo, a cassava and coconut cake that is a Surinamese dessert staple.

Three quarters of Suriname’s population reside in Paramaribo and its suburbs; beyond the capital district, roads are few and far between. Save for a coastal strip that extends across the northern border, more than 80 percent of the country remains swathed in rainforest, accessible only by plane, or by a network of rivers pocked with rapids.

Heading west by pavement along the country’s marshy seacoast, we pause at roadside stalls for smoked fish, fresh coconut water, and cassava chips. In Coronie district, beekeepers offer parwa honey for sale, which proves irresistible with its flavour of black mangrove nectar. As we approach Nickerie, the landscape opens into broad rice fields, farmed by artisanal producers as well as the efficient Manglie corporation — who take rice production to unusual new heights, literally, by sowing and treating their crops by airplane.

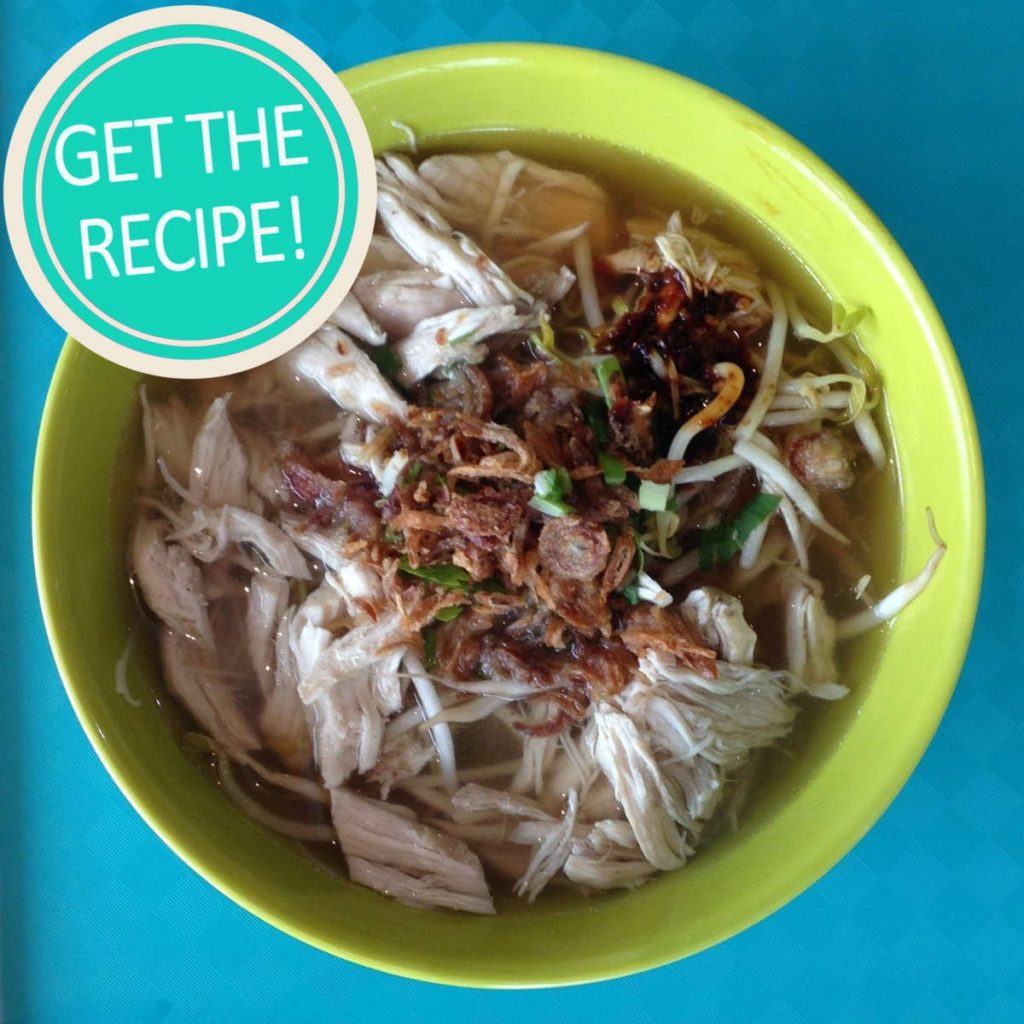

Our destination is Bigi Pan, a 680-square-kilometre wetland that hosts annual migrations of over half a million shorebirds and a nesting ground for scarlet ibis. Clouds of pink flamingoes wheel over the main lagoon, and in the mangrove along the 8.5 kilometre access canal, we spy pygmy kingfishers, lineated woodpeckers, and kiskadees. Our accommodation — a bare hammock shed on stilts in the middle of the lagoon — poses particular challenges for cooking. But chef-guide Rogier Wiratma proves up to the task with a pot of iconic Javanese saoto, rich with chicken broth, galangal, and lemongrass, topped with crisp vermicelli, bean sprouts, and hard-boiled egg.

From Nieuw Nickerie, a trip up the Corantijn River brings us to the indigenous Amerindian villages of Oreala and Klein Kwamalasamutu. Here we are treated to a dance performance and a traditional meal of pepra watra: a soup of cassava water and Madame Jeanette peppers, into which we are encouraged to crumble pieces of crispy cassava flatbread. While fish is the standard protein in this dish, our version features paca, a large rodent that is widely hunted. The soup is a delight for those with a yen for habanero-like heat; the chaser of casiri (cassava beer) we deem an acquired taste.

Access to Suriname’s wild interior is provided by a nascent eco-tourism industry, which ebbs and flows with the country’s economic and political tides. The ebb is apparent at Brownsberg Nature Park, a mountain preserve woven with hiking trails and sparkling waterfalls — but whose research facilities show obvious signs of decay. Howler monkeys sound their hair-raising chorus regularly here, and a small troop appears in a treetop one day. Agoutis, toucans, and black curassows make appearances, too, and night brings a symphony of toads and tree frogs.

The economic ebb gets more personal at Blanche Marie, where the once-flourishing Guesthouse Dubois, with its riverside cottages and alfresco dance-bar, has withered to a dream that died with its owner. Accommodations may be reduced to hammock shelters and a self-catering kitchen, but the dual treasures of Blanche Marie and Eldorado Falls, and a forest endowed with eight monkey species, still draw those willing to tackle 315 kilometres of dirt roads and 4×4 track. Here, Cook Rogier comes through again, with bruine boenen — hearty Dutch-Creole beans, laced with salt meat and allspice.

We probe still further into the country’s interior. On the Upper Suriname River, we motor by korjaal (dugout canoe) past villages from whose shores women wash laundry, dishes, and children. The women’s bright pangi wraps whisper of Africa — and well they might. This is the realm of the Saamaka, the largest subgroup of the Maroon people, descended from slaves who escaped plantations in the 17th and 18th centuries to carve their own communities out of the jungle. Upstream, the remarkable Saamaka Marron Museum provides insight into the rich African traditions that persist here.

Some villages offer rustic tourist accommodations. Our package at the comfortable Anaula Nature Resort includes medicinal plant walks, village visits and night-time caiman spotting. But as the first tourists to stay at Semoisie village, we are embraced by its residents, coached in cassava breadmaking from garden plot to woodfire griddle, and plied with homey Maroon cooking featuring the bounties of the season: sweet potatoes and pumpkins, river-fish and chicken, tajerblad and bananas, and everything peanut.

Back in Paramaribo for our final meal, we head to the Blauwgrond district to restaurant Jakarta: Taste of Java. The gracious decor and refined menu are a stark contrast to our upriver noshing — but a fitting end to our tour of the country’s cultural, culinary, and geographic potpourri. Like Suriname itself, my ajam daging santen (redolent with curry, coconut milk, and local vegetables) is multi-layered and globally-inspired — and begs for a return sampling.

CATHERINE VAN BRUNSCHOT is a Calgary-based writer who contributes regularly to TASTE & TRAVEL. Read more of her work at www.catherinevanbrunschot.com