“For me, the Andes region is one of the most fascinating regions in the world. It’s a world in its own right,” says Martin Morales, restauranteur, chef and author of Andina: The heart of Peruvian food: recipes and stories from the Andes.

There are some parts of the world that have a profound effect on us, because they are so extraordinarily different from all we have previously known. For me, Peru, and particularly the remote, rugged region of the high Andes, was such a place. This spare, lofty land, enfolded by jagged mountains at an altitude that leaves you gasping, seems indeed like a world apart — a secret, soulful place on the roof of the world.

Macchu Picchu is the main reason that tourists come to this part of Peru, where until the Spanish came in search of gold, the Inca civilization flourished in spectacular isolation. Their ruined city clings to the slopes of an impossibly vertiginous peak, as close to the gods as these ancient people could be. Their culture was rich, their agricultural science highly sophisticated, and their cuisine well developed.

Flying in to Cusco, descending through a narrow cleft in the Andes into a high mountain valley, is a spectacular experience. With cobblestone streets and a handsome Spanish cathedral, Cusco is a picturesque colonial capital. But it is also a modern city with cutting-edge restaurants riding the Nuevo Latino culinary wave that started in Lima with chefs like Gastón Acurio and has since swept around the world. But travel a few miles into the countryside beyond Cusco and you will find farmers tending fields of corn and quinoa, their dwellings simple adobe houses with earthen floors, an open hearth for cooking and guinea pigs scurrying under foot, waiting their turn in the pot. Cuisine is rustic, peasant fare, based on indigenous ingredients, many of which are unique to the region, and a nose-to-tail philosophy that sees nothing go to waste. How, I wondered, when I picked up Morales’ book, can a cuisine so deeply rooted in place be translated for an international audience?

Unlike other recent cookbooks that celebrate modernist Peruvian cooking, Morales focuses on the traditional home cooking of Andean women – (the Andina of the title). And he is quick to point out, there are eleven regions in the Peruvian Andes, each with its own climate, topography and gastronomic identity. Morales doesn’t attempt a comprehensive survey of Andean cuisine but presents a representative selection of recipes either from, or inspired by, each region.

It’s this pragmatism that makes Andina a successful cookbook. With four popular Peruvian restaurants in London, Morales has had ample opportunity to test his recipes, tailor them to available ingredients and make them palatable to diners in one of the world’s most sophisticated restaurant cities. And since the recipes are rooted in domestic cookery, they translate well for the home cook.

To be honest, I won’t be roasting a guinea pig, simmering a lamb’s head, or digging a pit to cook Panchamanca over hot stones, but if you are inclined, Morales tells you how to do it. I’m glad these recipes are included because they provide insight into traditional Andean cuisine, at the same time underscoring the authenticity of Morales’ approach.

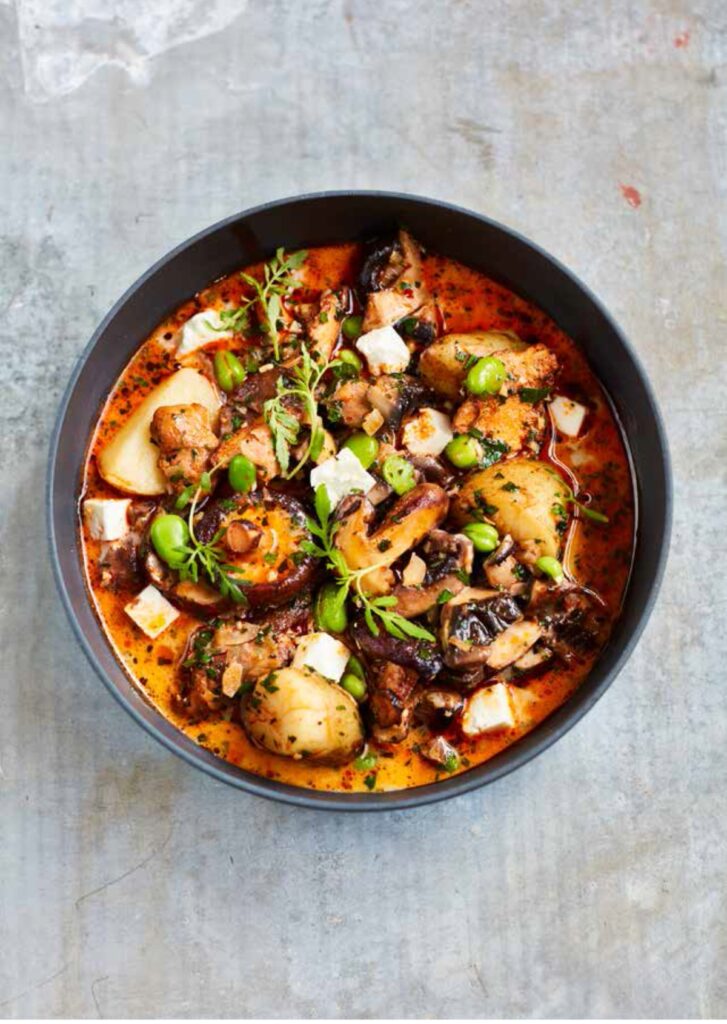

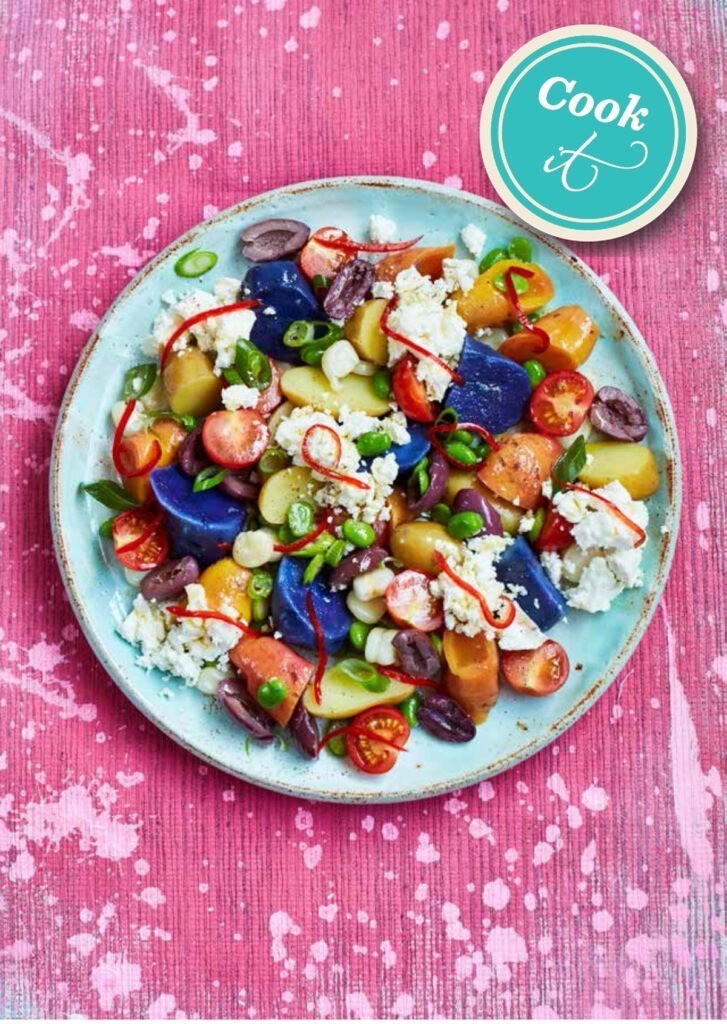

At the other end of the scale are recipes that may be unfamiliar but are well suited to weeknight cooking. All the recipes I tested, I’ll be making again. Pesque de Quinua, a savoury quinoa pudding laced with cheese, is comfort food at its best and an interesting way to cook the quintessential Peruvian grain (risotto style). Solterito, a salad of broad beans, tomato, feta cheese, olives and purple potatoes is as tasty as it is colourful and substantial enough to stand on its own for lunch or a light supper. Kapchi de Setas, a soup/stew of mushrooms with a kick of chile, is earthy, complex, and delicious. Picante de Huevos (Fiery Eggs), which Morales says is a favourite brunch dish at his restaurant, is a knockout.

There are a few key ingredients you’ll need to seek out in order to capture the unique flavours of Peruvian food. I found panca chile paste and aji amarillo paste in a Caribbean grocery store but if there is none in your neighbourhood, Morales gives instructions for how to make them from scratch. For harder to obtain ingredients he suggests substitutions (such as coriander, tarragon and mint for the fresh herb huacatay). The only hiccup I encountered was with using feta in place of queso fresco. Feta is quite a bit saltier than Peruvian (or more widely available Mexican) queso and while it is fine used as a garnish, it can overwhelm when used in quantity. If you’re making Pesque de Quinua, I’d suggest using replacing half the feta with cottage cheese.

Andean cuisine makes abundant use of vegetables and there are plenty of recipes in Andina that will suit non-meat eaters. There are chapters on salads and soups, and one dedicated to ceviches, including the sassy Peruvian version called tiradito. Breakfast and dessert offerings are creative – think Sweet Potato Pancakes with Coconut Whipped Cream from the Desayunos (breakfast) chapter and Cheese Ice Cream from Postres (desserts).

Eleven stories (one from each Andean region), with charming watercolour illustrations close out the book. In these heartfelt tales we come to know the people of the Andes through Morales’ eyes and his deep attachment to the ancestral culture of his homeland. They make sense of all that has gone before.

See all of our cookbook reviews on Pinterest!