The throbbing centre of Marseille life is le Vieux Port, the Old Port, where hundreds of fishing vessels and pleasure boats bob on the blue water, masts swaying in the breeze.

In the morning, grizzled fisherfolk line the quai des Belges to sell their ultra-fresh catch from large ice-filled vats, as they have been doing for generations. Just behind is the ultramodern Ombrière canopy in polished steel by architect Norman Foster, reflecting the bustling seaside activity.

France’s oldest city has been an arrival point for newcomers since around 600 BCE, first settled by the Phocaean Greeks, then the Romans. Under Louis XIV, Marseille became France’s leading port. This is also where the Great Plague of 1720 arrived and then spread through Europe, wiping out 45,000 Marseillais in its path.

Immigrants later arrived from Spain, Italy, Algeria and Tunisia, giving the city a cosmopolitan spirit that remains today.

This melting pot of cultures is also reflected in a rich and varied cuisine, from the famed bouillabaisse to couscous, to simple street food like panisse — fried chickpea dough, a local stand-in for French fries.

Marseille is now a sprawling city, the second largest in France, but its tourist and coastal areas are easily navigable by tram, bus, subway, and, most agreeably, on foot.

On the quays lining both sides of the Old Port are cafés, restaurants, bars with fishermen sipping pastis, and shops selling savon de Marseille. At the mouth of the port, two imposing forts face each other: Saint-Nicolas on the south and Saint-Jean on the north.

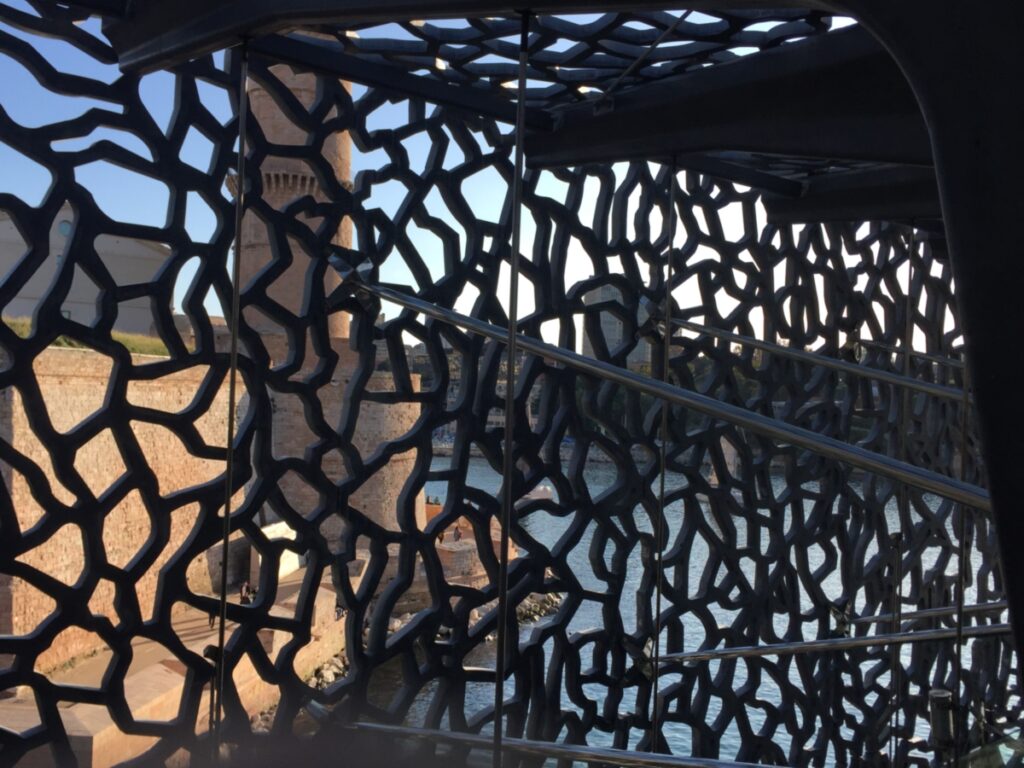

Fort Saint-Jean, its oldest remaining tower built in the 15th century by Good King René, is a great place to begin a history lesson, as it is now attached to the spectacular Museum of European and Mediterranean Civilization, or MuCEM.

The museum, designed by Rudy Ricciotti, was part of an extensive rebirth of the city in preparation for 2013, when Marseille was fêted as the European Cultural Capital. A number of temporary exhibitions augment the permanent displays of the history of the Mediterranean. Equally enjoyable is a simple stroll around the stunning terrace with incredible views through the filigree canopy — to the fort, the sea and in the other direction to the imposing neo-Byzantine Cathédrale de la Major.

Marseille’s most starred chef, Gérald Passedat, who thrills diners at his flagship restaurant Le Petite Nice, is in charge at MuCEM of a simple buffet-style restaurant and café called Le Môle.

Steps away from MuCEM, it’s fun to wander through le Panier, one of Marseille’s oldest districts, with its narrow, meandering alleys. The area was traditionally the first stopping point for waves of immigrants. Centre de la Vieille Charité, a former orphanage, is now a beautiful cultural centre, home to a range of exhibitions — one on Picasso on a recent visit – its enjoyment enhanced by the peaceful atmosphere of the courtyard surrounding a splendid chapel.

Back on the popular quai du Port, it can be tricky to find a great meal among the myriad restaurants lined up cheek by jowl. On a sunny day, the terrace of Au Bout du Quai, just down from fort Saint-Jean, is most inviting for its creative fish dishes. We sampled cod brandade with potatoes, pickled vegetables and pied de mouton mushrooms followed by rouget (red mullet) stuffed with herbs and beautifully presented on a bed of risotto topped with a flavourful emulsion. The soupe de poisson is also delicious, everything enhanced by the view of the port and of Notre-Dame-de-la-Garde basilica, poised majestically on the hill opposite.

Further down the quay, La Caravelle is a popular watering hole with locals, hidden up on the second floor of Hotel Bellevue, with funky nautical décor. Lucky for you if you can nab one of the few tables on its miniscule terrace with idyllic harbour views, where lunch features simple Provençal specialties like traditional aioli (garlic mayonnaise) served with cod and vegetables; petits farcis (stuffed vegetables) and a variety of fresh fish.

Originally, bouillabaisse was a humble fish stew prepared by fishermen using unsold fish of the day, simply boiled in seawater. Today it is one of Marseille’s prized delicacies available at many posh seaside restaurants, sometimes elaborated with luxury ingredients like lobster, turning this poor-man’s soup into something really over-the-top. In addition, many inferior versions abound, so in the 1980s, Chef Christophe Buffa of Le Miramar restaurant on quai du Port, and ten other restaurateurs, instituted the Marseille Bouillabaisse Charter to ensure the authentic bouillabaisse is prepared in a specific fashion, utilizing only certain ‘noble’ fish. You can see a little sign with the charter posted in many restaurants today, proving they are following the rules.

The noble fish normally consist of rascasse (a very ugly scorpion fish); rouget grondin (a type of red mullet); galinette (gurnard); Saint Pierre (John Dory); vive (weever); and congre (conger eel). The broth is made from local small rockfish; three variations on fennel: the vegetable, fennel seeds and a splash of Pastis; tomato; and orange zest, all boiled, reduced, then strained in a sieve. It’s a splendid dish presented in two filling courses: the soup, followed by the fish, served with toasts, which will be rubbed with garlic, dolloped with sauce rouille (spicy garlic mayonnaise) and grated Gruyère, then dropped into the soup to enrich it. Le Miramar remains one of the top tables to enjoy une vraie (a true) bouillabaisse, especially on the terrace overlooking the port in fine weather.

And I highly recommend the entertaining and hands-on bouillabaisse cooking class with chef Buffa!

But excellent bouillabaisse and other fine fish specialties can be found further down along the corniche, our favourites including L’Epuisette, Le Péron, and Chez Fonfon on the adorable harbour called Vallon des Auffes.

High winds, that infernal Mistral, prevented us from venturing out on a boat to explore the spectacular coastline, the famous calanques (fjord-like inlets), and Chateau d’If, made famous in Alexandre Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo. But that meant we were able to lunch at a new hotel-restaurant on the corniche, Les Bords de Mer, for simpler but still delicious fish dishes.

While looking out to sea and admiring the incoming ferry from Corsica, we enjoyed ultra-fresh carpaccio of line-caught mulet (grey mullet) garnished with capers, brown butter and smoked vinaigrette, followed by sea bass served with an intriguing combination of roasted fennel and cabbage, napped in a dark jus de daube (sauce of beef stew) garnished with fried sage leaves.

In 2019 Alexandre Mazzia was named Chef of the Year in France by the respected Gault & Millau guide. His] His towering figure dominates the small counter on view at his modest and refined restaurant called AM par Alexandre Mazzia, where he deftly and gracefully plates an astonishing array of tiny dishes, mostly based around vegetables and fish, in a series of surprise menus he calls “voyages.” Our excursion (the shortest) consisted of 27 exquisite dishes served in harmonious groupings. His cooking philosophy arises from a love of smoke, roasting and spice, influenced by his early upbringing in the Congo. Signature dishes include inventive combinations like smoked eel with chocolate; wild salmon and trout roe with smoked milk; even the raspberry sorbet palate cleanser is heightened by a lick of harissa. Mazzia himself is humble and soft-spoken as he accepts accolades from admiring diners.

Pizza is as ubiquitous in Marseille as in any large city, but Marseille can claim authentic bragging rights, given its large Italian population. Our Marseillais friend of Italian roots enthusiastically recommended La Mère Buonavista, a casual institution known to locals, near Place Castellane. The Sicilian family opened the place as an ice cream parlour, but it is now known for its fire-licked, chewy pizzas with an array of simple toppings. We loved one garnished with figatelli, a flavourful Corsican liver and pork sausage (Marseille is also a landing place for people from that picturesque island just to the south).

Soap has been hand crafted in Marseille for over 600 years, typically following a special technique involving long boiling in a copper cauldron. While there were once hundreds of small factories making the famous savon de Marseille, today there remain only four: Fer à Cheval, Marius Fabre, Savonnerie du Midi (La Corvette) and Savonnerie du Sérail, plus numerous cheaper copies found at any street corner or market stall. To identify the authentic item, look for the stamp indicating 72% oil plus the stamp of the maker.

The dark green olive oil-based square bar is highly revered for bathing, of course, also laundry and general cleaning, but also for other near-miracle properties: jewelry shops recommend it to gently clean delicate chains and pendants, while others extol its virtues as an efficient spot-remover on fabrics.

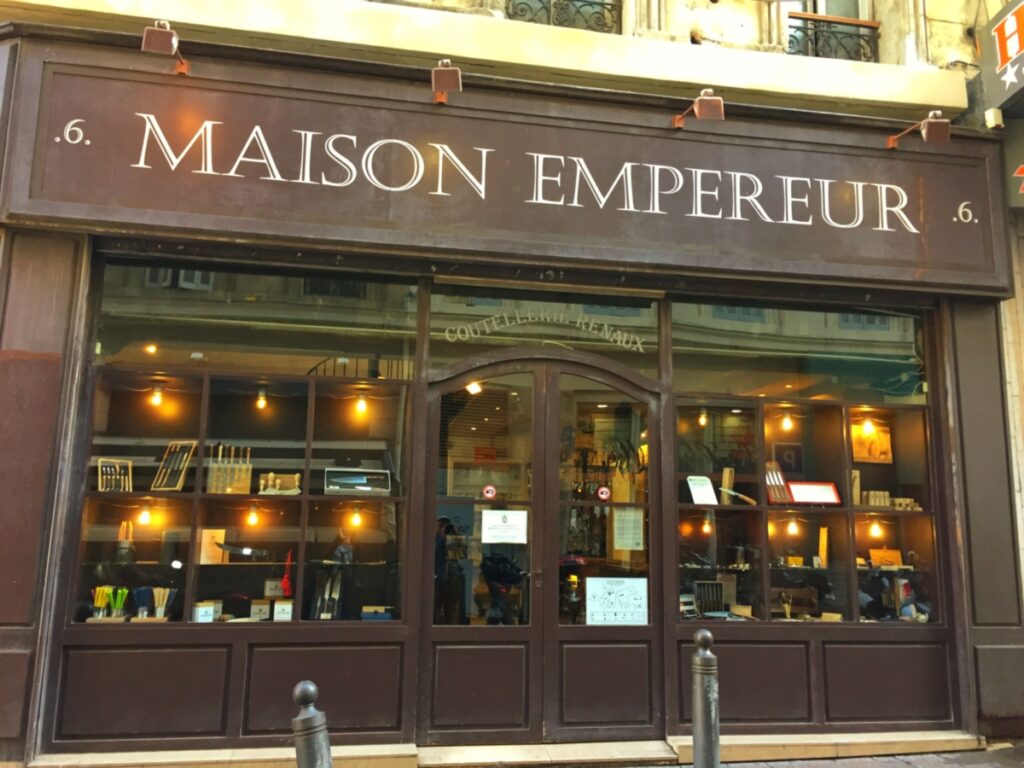

Soap is just one of thousands of items available at France’s oldest quincaillerie, (hardware store), Maison Empereur, established in 1827, still fully functioning and beguiling with its creaky wooden floors and old cabinets, popular with locals and visitors alike. The old-fashioned shop is a huge maze of small fascinating rooms, chock-a-block full, each dedicated to a special household category: for example, fancy or practical cookware; brushes of every shape and texture; tools; decorative items; even antique toys. So if you’re looking for a child’s butterfly catcher, for example, you’ve come to the right place.

It’s located near La Canebière, the main thoroughfare, named for canèbe, the Provençal word for hemp, after a hemp factory once located there (though some claim the street was named for the American soldiers who strolled down the street drinking cans of beer!). Nearby the vibe is quite a contrast to the Old Port with the lively marché de Capucins, surrounded by many North African groceries, bakeries and couscous restaurants.

A short climb brings you to atmospheric cours Julien, a bit edgy, where graffiti-splashed buildings have been turned into cafés, casual bars, theatres and cozy restaurants such as le Bistro du Cours. On weekends, children play around the pleasant fountain and evenings are enlivened by a relaxed young crowd.

La Joliette is another waterfront neighbourhood experiencing a revitalization. Ferries still depart from here to Corsica. Hotels and a shopping mall, Les Terraces du Port with fantastic coastal views, have popped up, and the abandoned 19th-century warehouses have been transformed into a buzzing marketplace called Les Docks with shops and eateries.

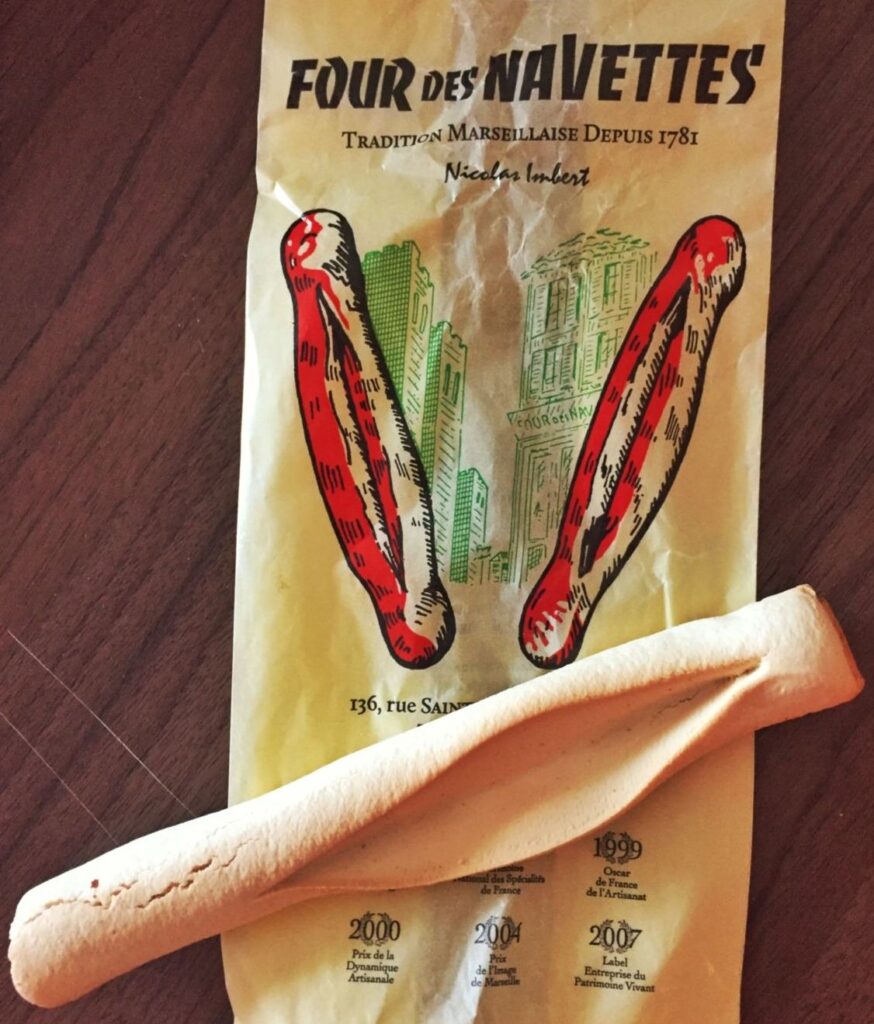

In Marseille one always has the feeling of being near the sea, so it is no surprise that one of its signature confections is a boat-shaped crunchy cookie called a navette. The oldest bakery in Marseille, Le Four des Navettes, is found on the route leading up to the medieval Abbaye de Saint-Victor – well worth a visit for its sober interior and ancient crypt carved out of the rock.

The bakery, acknowledged as part of the local cultural heritage, has been crafting navettes in its vaulted oven since 1781. Now in the hands of the Imbert family, the secret recipe has been passed down through the generations. The cookies are seductively flavoured with orange blossom, and we happily float away over the blue Mediterranean waters, enchanted by its heavenly scent.