Composition and good photography go hand in hand. In this column I’ll discuss composition with a special focus on lines.

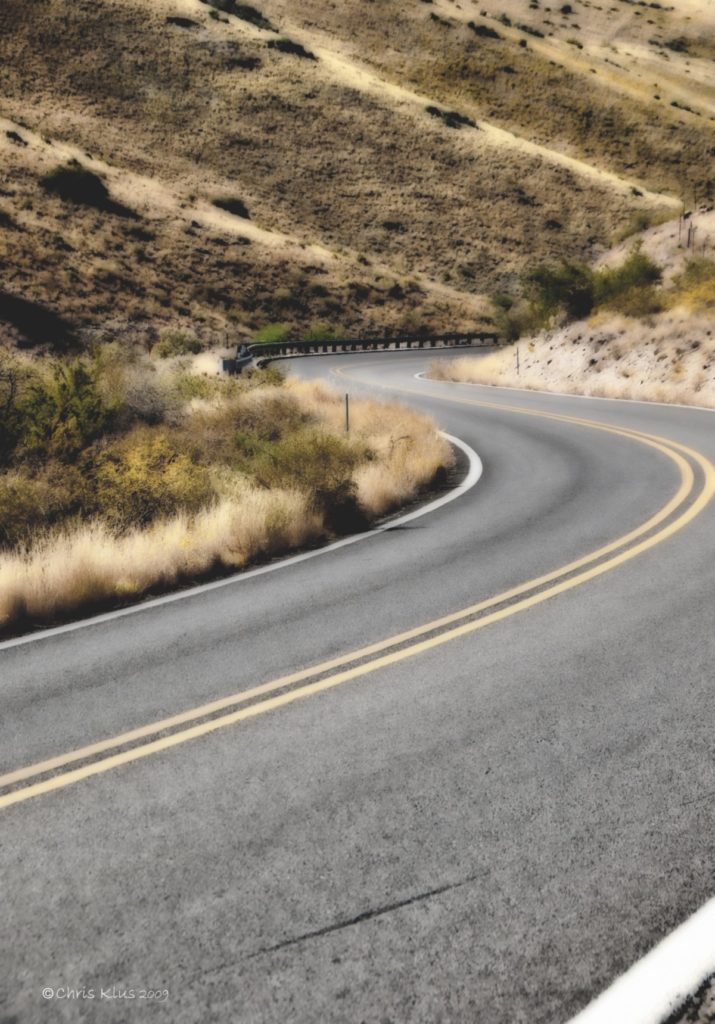

First, the concept of leading lines — one of the most effective and under-utilized compositional tools available to photographers. When viewing an image our eyes tend to enter the image from left to right—the same way we read text. (I’ve been told that people from cultures that write from right to left tend to enter an image in that direction, but I can’t confirm this.) Alternately, our eyes will want to enter the image from bottom to top. In any event, our eyes look for something that will lead us into an image; thus the concept of the leading line. And once you enter the image your eyes will look for more lines or other objects to follow within the image. Lines can be used to draw the viewer’s attention to (or sometimes away from) the subject of your photograph.

At the heart of photographic composition is graphic design — the art of visual communication. Lines are graphic elements that some say have meanings of their own. Vertical lines can stimulate feelings of dignity, height, grandeur and strength while horizontal lines usually denote a response of calmness, tranquility and peacefulness. Curved lines are all about beauty and charm and lines like the letter S speak about grace and balance.

Implied lines are not actual lines that you are used to seeing. They can be an object that will capture your eyes and move them into the image. These lines can be straight, diagonal, wavy, or any other creative variation. Take a look at the images in this article and be attentive to how your eyes move into and within the image. You need to be aware of this when composing images and consciously look for these lines.

Lines are also an important way of defining spaces in an image. In a previous column I talked about the rule of thirds where the major elements of the image should be distributed in thirds, either vertically or horizontally, within the image. For example, the horizon in a landscape image is the line that separates the ground from the sky.

Another aspect of lines is perspective. A straight-on photo of a tall church may be nice but a more interesting shot is coming right up to it and shooting upwards. This perspective makes the lines of the church converge and your eyes move upwards in the image giving a stronger sense of the height. Perspective can also create depth in an image by having lines converge in a distance — especially if they lead to the subject of the image. This type of perspective works best using long focal length lenses (greater than 200 mm) as they compress distant objects, and also by varying the camera-to-subject distance.

On the other hand, to give a picture a sense of space or vastness you should use a wide-angle lens which will not only capture a wider aspect of the subject but the distortion produced by these lenses (especially fish-eye type lenses; e.g. less than 10 mm) projects a sometimes pleasing otherworldliness. That’s because of Barrel distortion which causes images to be spherized and the edges to look curved and bowed to the human eye. It almost appears as though the photo image has been wrapped around a curved surface. It is most visible in images that have straight lines in them, as these lines appear to be bowed outward.

And lots of lines in an image, whether straight or wavy or jagged, can create patterns that either lead the eyes to the principal subject(s) or are abstract and pleasing on their own. Often macro images (extreme close-ups) are full of lines and almost look abstract.

Understanding how to use lines in your photography is a great tool for creating stunning images. If you harness the power of lines in photography you can elicit a response from your viewers. Often this response happens on a subconscious level but it’s still important to know how to use lines in order to achieve your desired response. A good photograph will almost always make use of one kind of line or another. So, go ahead and learn your lines.