Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings is best known as the author of the 1939 Pulitzer Prize winning novel The Yearling that describes the relationship of a young boy with his pet deer. But she was also a pioneer of female independence, carving out a life of self-sufficiency in the backwoods of Florida that was extraordinary for her time. And in her own estimate, a greater accomplishment than her writing was her skill in the kitchen.

Marjorie Kinnan was born in Washington DC in 1896 and showed early promise as a writer. She married journalist Charles Rawlings in 1919 and after visiting his brothers in north central Florida, the couple spontaneously bought a rural property near the present-day city of Gainesville and moved there. Charles didn’t last long as a gentleman farmer and ultimately returned north, leaving Marjorie to manage the farmstead and orange grove at Cross Creek. Marjorie fell in love with the unique landscape at the Creek and the local “Cracker” (backwoods Florida) style of living close to the land and to nature. She wrote a number of critically acclaimed books describing her life and that of her neighbours. Her one cookbook, Cross Creek Cookery, a collection of regional recipes and vividly rendered vignettes of domestic life at the Creek, was published in 1942.

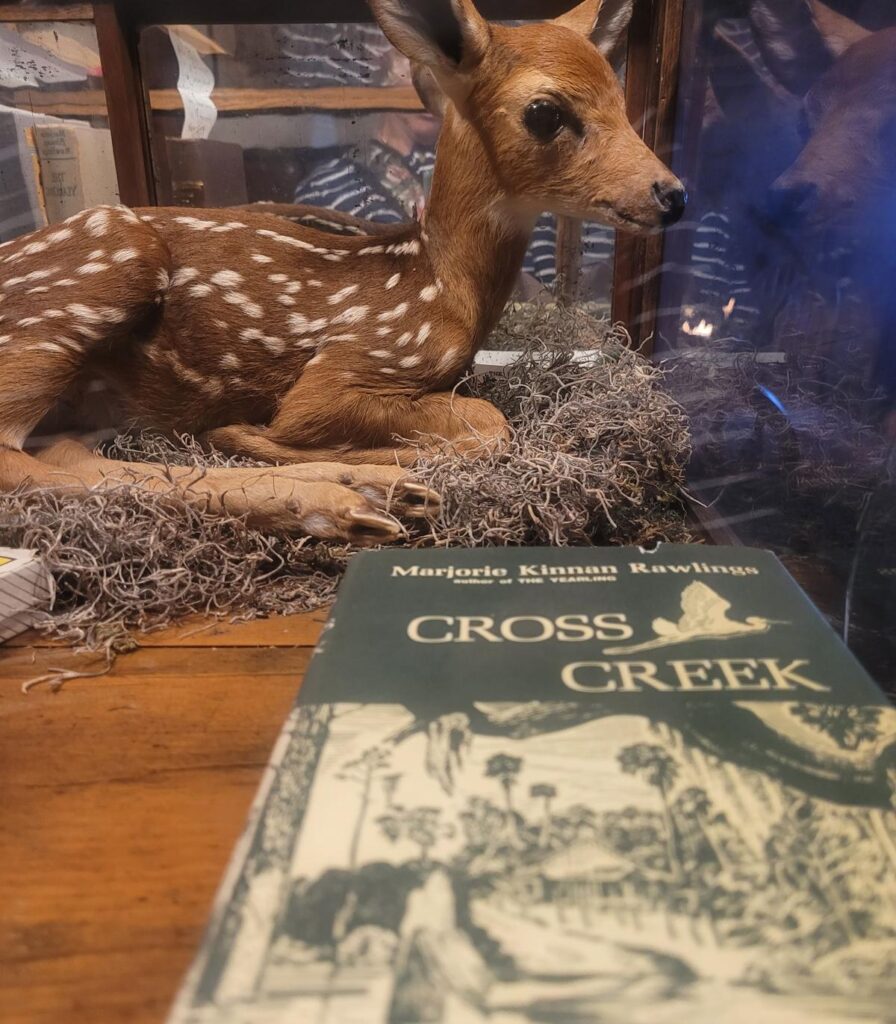

Rawlings’ farmstead, the oldest part of which was built in 1884, and the remnants of her citrus grove are now managed by Florida State Parks. The sprawling wooden farmhouse, surrounded by orange, grapefruit and tangerine trees, has been restored with original furnishings from the 1930s, along with some of Rawlings’ personal possessions, including her typewriter. Her kitchen garden has been replanted with the seasonal vegetables and herbs that supplied her table. Dora, the ill-tempered cow who produced especially rich cream, is long gone, but the barn in which she lived still stands and houses Rawlings’ yellow 1940s Oldsmobile. Ducks and chickens peck in coops in the yard, as they did in her day. Visiting the farmstead is like stepping back in time – the pantry is stocked with pickles and homemade jams, a recipe book stands open on the kitchen table and it feels as if Rawlings might come through the door at any moment with a teatowel in her hand or a basket of newly laid eggs.

Rawlings loved to entertain and with the help of her long-serving African American maid, Idella Parker, turned out impressive meals for the guests – many of them literary figures and celebrities of the day — who often came to stay at Cross Creek. These house parties were boisterous affairs, with copious amounts of food and so much alcohol being consumed that guests were sometimes too drunk to drive home. Rawlings herself had a cavalier attitude to driving under the influence, surviving at least five serious car crashes when inebriated behind the wheel.

Rawlings cooked on a wood-burning stove, working with ingredients grown, fished and hunted locally, often by her own hand. Cross Creek Cookery includes recipes for dove, quail, squirrel, rabbit, bear, alligator, turtle, frog and gopher – foods she learned to cook by watching her neighbours. She was particularly fond of blackbird pie but stopped making it when she learned that killing Florida’s red wing blackbirds was illegal.

Although she appreciated and embraced the frugality and ingenuity of the Cracker way of life, Rawlings didn’t abandon the elegant style of her former life in Washington high society. Her table was set with Wedgewood china and fine glassware. Dinners and “company luncheons” were multi-course affairs, planned with care and served with pride and aplomb in the formal dining room with its heart pine floors polished until gleaming. Rawlings always sat facing the window so her guests wouldn’t have a view of the outhouse.

Among Rawlings’ letters is a description of a meal served to friends that began with iced honeydew melon with lime juice, followed by roast wild duck, wild rice, carrot soufflé, fresh lima bean croquettes, whole braised small white onions, tiny cornmeal muffins with kumquat jelly, celery hearts, mango ice cream and devil’s food cake.

In 1942, when rationing of meat, sugar, canned goods and other foods had been introduced in Florida, Rawlings was still able to produce an impressive menu. A meal she served to a group of army doctors on leave included blue crabs she caught herself (served a la Newburg and plain with mayonnaise), baked sherried grapefruit, yeast rolls with guava jelly, carrot soufflé, tomato aspic with artichokes, peach ice cream and orange cake, all made from scratch.

Rawlings loved Cross Creek and took great pleasure in the natural surroundings that formed a backdrop to her meals. “Whenever the Florida weather permits, which is ten or eleven months of the year, I serve on my broad screened verandah,” she writes in Cross Creek Cookery. “It faces the east, and at breakfast time the sun streams in on us, and the red birds are having breakfast too, in the feed basket in the crepe myrtle in the front yard. A dilatory feeder, more interested in his art than his maw, sings from the pecan tree that shades the verandah. At dinner time, the sunset is rosy on the tall palm trunks in the orange grove across the yard. We have for perfume the orange blossoms in season, or the oleanders, or the tea-olive. We have for orchestra the red birds and mocking birds and doves and the susurrus of the wind in the palm trees.”

Cross Creek Cookery was written in response to requests from readers of Cross Creek, Rawlings’ memoir of life in rural Florida, which includes some mouthwatering descriptions of meals. Many of the recipes are intended for entertaining and contain lashings of cream and other rich ingredients. But there are also everyday recipes — making use of the ingredients that were available to Rawlings throughout the Florida seasons — that resonate with the farm-to-table ethos of today.