As a Kerala schoolboy my lunch box was a banana leaf, plucked from our garden, filled with food, folded over, and wrapped in a page of yesterday’s newspaper. It made a tidy, perfect parcel to tuck into a schoolbag.

Unwrapped at lunch break, there would be the pleasure of a still-warm meal, its flavor ramped up by the long contact with the fragrant leaf. Inside, perhaps an egg omelette, some cabbage thoran, a curry of black chickpeas in a thick tomato gravy, a piece of last night’s fried fish. One of my mum’s pickles would always be there, along with a spoonful of raita. And rice, of course, always rice. I would wolf it all down, then toss the leaf on the side of the road to decompose or, more likely, to be eaten by the temple cows that wandered free in our town. No plastic left behind, no food waste, and no bulky tiffin box to lug to after-school cricket practice.

As a kid, I would never have called this tasty muddle of food a thali — it was just my school lunch. But that’s what it was. Because a thali is a meal of many parts, which makes the contents of that leaf, modest as they were, count as one.

The format of a meal of many parts is simply the way we eat in India, the way we have eaten for centuries. Not to be confused with the more European style of a meal of many courses, but one that involves many elements, served together. The dishes are always hyper-regional and -seasonal, usually culturally or religiously significant, and typically presented on a round, rimmed plate (also called a thali) holding small metal bowls. Or, in my part of India, more often presented on a banana leaf.

Cooking thali might sound like a lot of work. And it sometimes is if the occasion calls for an eye-popping all-out feast in full-on splendor. But everyday thalis can be quite simple. Many dishes can be whipped up in fifteen minutes, recipes can be doubled, allowing leftovers for another day, and almost all can be made ahead, leaving the cook with little to do but make rice while the curries warm up for supper. With one or two anchor dishes, plus rice, the balance of a thali is made up of the small stuff—the condiments and accompaniments and sides that give the meal flavor, character, zing, and balm, usually found in jars or bowls in the fridge. No sweat, really.

As an Indian chef, the tradition of thali dominates my life. It is the way I eat at home, it is the way I celebrate life’s big events, and it is the style of cooking we offer at my second Ottawa restaurant, Thali.

My first cookbook, Coconut Lagoon, was a tribute to my home state of Kerala, an introduction to its unique cuisine, essential ingredients, and traditional dishes. It was written for all those unfamiliar with the particular pleasures of its particular cuisine.

I wanted this cookbook to showcase south Indian home cooking—the dishes my wife Suma prepares for our family, defined by seasonality, affordability, nutrition, and tradition, recipes passed down from grandmother to mother to daughter—and for the ways we create complete meals, those we serve on thalis at the restaurant.

The Art of Tempering Spices

Tempering, blooming, or crackling (called tadka) is a cooking method in which spices are added to hot fat, to extract their fragrance, perfume the oil, and add flavor to a dish. Spices are either tempered at the beginning of a recipe for a curry or a stir-fry, or at the end to finish a dish — a dal or a raita — with a flourish of sputtering spices. The process is not difficult, but tempering is a skill requiring a good nose and an eagle eye, best learned through practice and from making mistakes. The biggest mistake being that you may burn the spices. In which case, there is no remedy other than to start again with fresh spices and to be more vigilant.

As tempering can take only a few seconds, ingredients are added in rapid succession, and timing and temperature are everything, it’s critically important that you have a mise en place of measured spices and aromatics at the ready, near the stove. Also important is the right pan. If you are tempering spices at the beginning of a recipe, you’ll need a larger pan, preferably with a flat bottom and high sides, to continue building the dish. Tempering spices at the end of a dish will require a small frying pan or a tadka pan designed specifically for the purpose.

Start with hot oil or ghee and reduce heat to medium before adding the spices to help ensure they don’t burn. If spices do burn, toss them and start fresh.

You can briefly cover the pan with a splash guard or a lid to keep the spices from popping out of the pan but be prepared to remove it fast to continue with the recipe.

Excerpted from My Thali: A Simple Indian Kitchen by Joe Thottungal with Anne DesBrisay. Photography by Christian Lalonde. Copyright © 2023 by Thali Restaurant. Excerpted with permission from Figure 1 Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

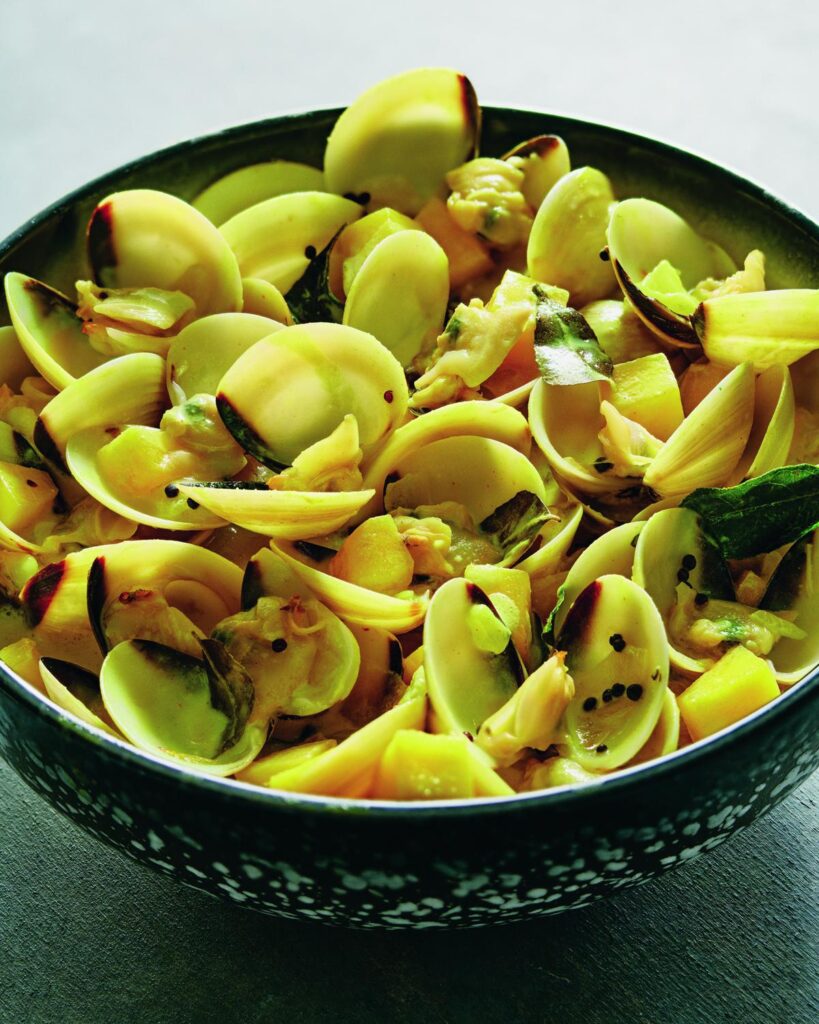

Steamed Clams in a Mango Coconut Sauce

Dal Makhani

Roasted Beet Salad

Mint-Lime Rickey

Cashew Balls

Oats Puttu

Food for Thought Curry