For cooks who long to visit the ends of the earth via pots and pans, big best-selling cookbooks from leading North American trade publishers can be an exercise in frustration. First of all, they seldom stray beyond a few popular travel destinations. And when they do, they work overtime to keep the shock of the unfamiliar to a pleasantly reassuring minimum.

The good news is that there are plenty of cookbooks from other sources capable of leading users on more adventurous kitchen voyages. Not just any users, though. You have to be game for the “adventurous” part, which involves the company of brave safari guides like Nur Ilkin and Sheilah Kaufman, the authors of The Turkish Cookbook: Regional Recipes and Stories.

This is Ilkin and Kaufman’s second book, and comes from one of the two chief publishers of cookbooks for food-minded North Americans trying to think outside the box: Interlink Books, located in Northampton, Massachusetts. The other, the New York-based firm of Hippocrene, published their first collaboration, A Taste of Turkish Cuisine.

Hippocrene is a prolific publisher of foreign-language dictionaries. It also regularly takes up culinary subjects too esoteric or non-commercial for anybody else — e.g., the cuisines of Bolivia, Lithuania, Albania, Uzbekistan, and Fujian province in China — and publishes labor-of-love works by people acquainted with the food in question. Interlink chiefly deals in books on politics, history, and travel, with special concentration on the Middle East. Its assorted cookbook titles mostly focus on the British Isles, the Caribbean, and the Middle East. Many (not all) are picked up from various overseas publishers and re-packaged here with new color photographs and some degree of editorial “Americanization.”

The online backlists of these two companies are the first place to look for books on most subjects outside the narrow purviews of the major U.S. and Canadian cookbook publishers. But you should know in advance that you can’t expect all the luxuries provided by the big guys — for instance, methodically vetted recipes with double-checked measurements and foolproof timings. Or, in many cases, directions based on reliable command of Western kitchen-speak.

Is there any compensation for these disadvantages? You bet. Unless they’re by someone like Paula Wolfert, North American books on far-flung cuisines usually take you by the hand and walk you through careful recipe-scripts in a manner resembling sanitized wildlife documentaries for easily scared kindergartners. And they can (mostly) be counted on to ignore vast swathes of the Far East, the Middle East, Latin America, Central Asia, and Africa. Books from the few outfits really interested in global culinary diversity present greater challenges. They’re useless to people who won’t go the extra mile (or several) in pursuit of understanding, invaluable to those who will.

The Turkish Cookbook is a perfect example of the tradeoffs you can expect. On the one hand, the recipes have many incidental roadblocks that the savvy editorial teams at mainstream cookbook publishers would have straightened out. On the other hand, the straightening-out process probably would have removed much of the book’s verve and originality. Not to mention that most trade publishers would have considered this particular project too esoteric to bother with.

No other English-language Turkish cookbook has taken quite the same tack as this one: a region-by-region culinary survey. It’s a wonderful idea for investigating the food of a land that stretches a thousand miles west and east from Greece to Armenia and Iraq, and that ranges through an incredible diversity of topographies including the vast Anatolian plateau, many different hill and mountain ranges, and three seacoasts.

Simply organizing the recipes by region of origin makes a huge difference to understanding various facets of the cuisine. Even people who already have one or more Turkish cookbooks are almost certain to come away from this one with a rearranged perspective on things they’ve encountered before.

A case in point: the famous dish called “Circassian chicken.” I was puzzled to find it represented in this book by a recipe from a cook in the Marmara region, at least seven or eight hundred miles west of the ancient Circassia. The mystery solved itself when I read Ilkin and Kaufman’s observation that over the years many people from eastern Black Sea territories like the home of the Circassians migrated into parts of the Marmara region. An analogy might be a person unaware that Basque dishes ever existed outside the Pyrenees suddenly grasping that Basques have been a Rocky Mountain presence for generations.

I don’t want to suggest that this work will be all things to all cooks. It might be seriously disappointing as anyone’s first book on one of the world’ most magnificent cuisines. Like many unorthodox and boundary-expanding cookbooks, it’s best used by sturdily motivated, somewhat experienced cooks who see themselves not as passive recipients of board-certified truth but as participants in unfinished searches for progressive insight.

Users must count on minor and major obstacles — for instance, the absence of maps. Of course, we can all go online and identify the many cities named in Ilkin and Kaufman’s geographical sketches. But it beats me why anyone capable of seeing the importance of a regional Turkish cookbook wouldn’t also want to present readers with a good, detailed map as close as possible to page 1. And while we’re on reference tools, the authors’ glossary of ingredients is both vague and unsystematic.

Cooks who expect cut-and-dried exactitude from all cookbooks will also be bothered by muddled culinary terminology (it isn’t clear that Ilkin and Kaufman understand the meaning of “puree,” and many people may blink when “turnover” turns out to mean a layered rice dish reversed onto a plate). They will also have a hell of a time producing homemade yogurt from a recipe telling them to “make a well” in a pan of heated milk. Or essaying that Circassian chicken recipe without knowing how much chicken stock to add to the walnut sauce — certainly not the whole six-plus cups!

I was pretty annoyed myself at finding only the most perfunctory aid on exploring Turkish food stores like the ones in my New Jersey neighborhood. They would be gold mines for users of this book interested in understanding and searching out some important items — e.g., “red pepper paste” = biber salcasi; such-and-such are the main fresh or ripened cheeses that Turkish people would use in such-and-such recipes; this is how to look for rich, creamy yogurt. Ilkin and Kaufman seem only half aware of what really devoted English-speaking fans of Turkish food might want to know.

But as someone says in the last act of Our Town, “that ain’t the whole truth and you know it.” Most of the foregoing criticisms could never apply to many smoothly produced but sometimes vapid works from the foremost cookbook publishers in the land. No such pat spoon-feeding exists here.

Ilkin and Kaufman’s recipes don’t just repeat the few kinds of broiled meats and meze, soups and salads that you’re going to find in any neighborhood kebab restaurant and any Turkish cookbook. Without this work, I wouldn’t have known that people from the southern Turkish city of Gaziantep (not far from the Syrian border) cook mung beans and also love the smoky-flavored roasted green wheat (freekeh, firik) so popular in Egypt. Or that there’s a “corn belt” along the Black Sea shore where cooks are devoted to local versions of polenta and commonly fry fresh anchovies in a cornmeal coating. Or that anyone in Turkey liked daikon radishes in a salad.

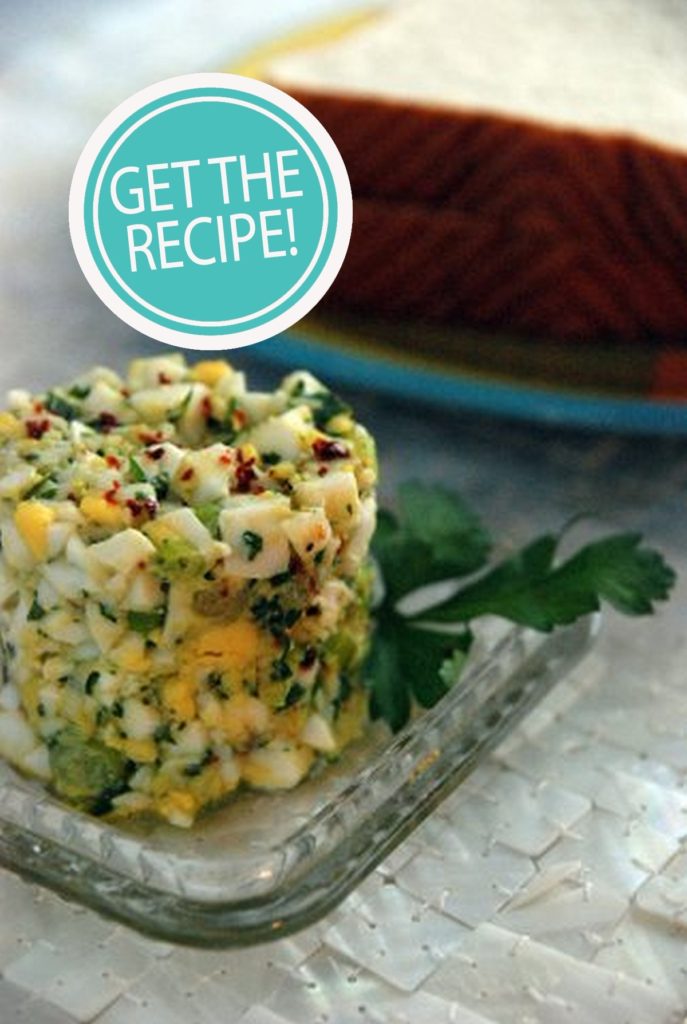

I had good results in the kitchen, by dint of keeping my thinking cap firmly in place. A heavy mashed potato salad needed more liquid (I ended up lightening it with some of the potato cooking water) and less tahini. More successful were a very simple can’t-miss egg salad, a fine dish of sauteed grated zucchini with walnuts and yogurt, and a lovely fresh-flavored orange pudding (for some reason labeled “curd”). The most wonderful of all was also the hardest: keskek, a slow-cooked wheat porridge said to be a staple for celebrations like weddings. It took me about three times the suggested 10 – 15 minutes to beat the cooked mixture to the right thickness, but the creamy, silky texture of the starch that dissolved out of the wheat made it worth every second.

The bottom line is that though novices should go elsewhere, this is the most adventurous English-language cookbook available for seasoned cooks who have already fallen in love with Turkish food.

Anne Mendelson is the author of Stand Facing the Stove: The Story of the Women Who Gave America The Joy of Cooking (Henry Holt, 1996) and Milk: The Surprising Story of Milk Through the Ages (Knopf, 2008).